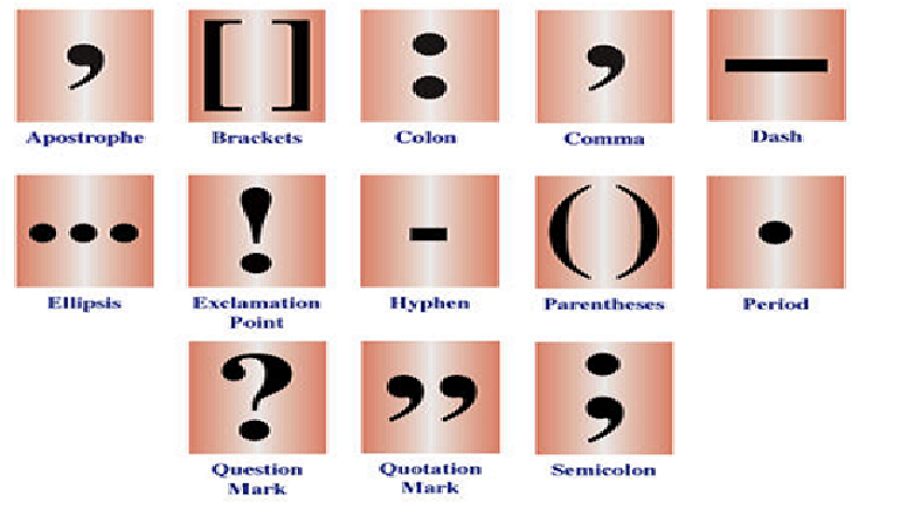

For those of us who love sentences, for those who roll words on our tongues like cherry Lifesavers (and who doesn’t?), punctuating sentences often comes naturally, like breathing. However, for many students—even my college students—punctuation’s a guessing game, a boring quest to place a comma, apostrophe, semi-colon, or period precisely where it belongs. A surprising number of students I’ve taught in over 25 years of college instruction don’t know how to write a sentence without at least an error or two, and most of the time these errors involve punctuation.

Punctuation is inherent, of course, in our ability to read and write sentences with clarity so our meaning doesn’t get misconstrued. Correct punctuation tells the reader where one

thought ends and another begins. It allows the reader to pause and collect his thoughts about what he’s reading. When punctuation is haphazard or non-existent, the sentence is flawed, like a shirt that’s stained, a hair out of place, crumbs in a gentleman’s beard. The writer’s and, hence, the reader’s ideas about the writing become muddled.

Now, I wasn’t always this persnickety about punctuation. In fact, early in my career I was clueless as to where a comma and a semi-colon went (though in my defense, I’ve never punctuated British-style in my life!). Perhaps I fell asleep in eleventh grade English class when dear Mr. Boloker started diagramming sentences. More likely, I was dreaming about Peter Frampton and wondering how I might procure backstage passes to one of his concerts.

But back in the days of my misspent youth, I was 24, working as an editor’s assistant at Woman’s Day magazine, and haphazardly jotting commas down in my sentences to the point where the editor asked me what the heck I was doing. Duly chastised, that evening I consulted my college grammar text, and my punctuation improved. However, it wasn’t until I started teaching several years later and assigned my students Pamela Arlov’s Wordsmith and Paige Wilson and Teresa Ferster Glazier’s The Least You Should Know About Writing that I felt confident in my punctuation prowess (and my alliterative abilities improved as well!). If you’re so inclined, both the above texts are worth the money, particularly the second one. The chapters are short, the instructions clear, and the exercises help reinforce each chapter’s main objective.

Even in writing this post, I confess I noticed faulty punctuation in several prior drafts. Punctuation is hard—it’s persnickety! And that’s why we must be extra mindful of it.

CRUCIFY THE COMMA SPLICE!

Seriously, when did it become okay to connect sentences with just a comma? This is called a COMMA SPLICE, and it’s a big NO-NO, punctuation-wise. As with British-style punctuation being used by North Americans writing and publishing in the good ol’ U.S. of A. (read upcoming rant—ie: blog post—on that!), authors seemingly everywhere are committing this grievous error, thereby contributing to the punctuation problem. Now, true, it’s not on the same level as climate change, but if one hopes to be literary, one should avoid such a

faux pas. I get why some established and/or highly skilled authors use just a comma to connect certain sentences, apparently because it keeps the rhythm of the sentence moving. If, instead of a simple comma, you use an ellipsis repeatedly to help show the connection between ideas, well, those three little dots would soon be quite distracting. Use just one dot instead! The comma splice is ubiquitous—it’s in novels, literary journals, all over the internet, and again, it’s an error that writers would do well to avoid.

The simple, lonely period indicates that the writer’s idea for that sentence is finished, and it gives the reader a moment to comprehend this, connect with said writer’s idea and move onto the next idea in the next sentence. Writing a few straightforward declarative sentences in succession is fine. You won’t sound like you’re back in first grade. On the contrary,

you’ll sound clear, intelligent, and your reader will be able to grasp your meaning effortlessly.

The comma splice virus is kind of like multi-tasking. Society has grown accustomed to doing more faster, often without the opportunity for deep thought (or sometimes, any thought) to occur, so concerned are we with getting it all in, all done, quick, quick, quick, no time to search for the period or semi-colon keys when it’s just so comfy to put one’s middle finger down a row, depress the comma key, and hurry onto the next run-on like a literary jackrabbit.

Often, as I previously mentioned, you can use a semi-colon instead of just a comma to connect two independent clauses provided the clauses are related in subject matter. For example, you could write the following:

T.C. Boyle’s story “Greasy Lake” depicts three young men who consider themselves “dangerous characters”; they soon realize that being dangerous isn’t quite as alluring as they once thought it was.

You could also write the exact same independent clauses (ie: complete sentences) with a comma between them as long as you follow that comma with a coordinating conjunction, known in punctuation vernacular as the acronym fanboys (f=for; a=and; n=nor; b=but; o=or; y=yet; s=so). Hence, you could take the same sentence and structure it this way:

T.C. Boyle’s story “Greasy Lake” depicts three young men who consider themselves “dangerous characters,” yet they soon realize that being dangerous isn’t quite as alluring as they once thought it was.

Finally, of course, you could take the same two independent clauses and simply put a period between them, thus making one sentence two:

T.C. Boyle’s story “Greasy Lake” depicts three young men who consider themselves “dangerous characters.” They soon realize that being dangerous isn’t quite as alluring as they once thought it was.

Notice the clarity and sophistication of the two sentences separated by a period is as evident in the above example as it is in the prior two. Nothing is lost when one simplifies and ends a sentence with a period.

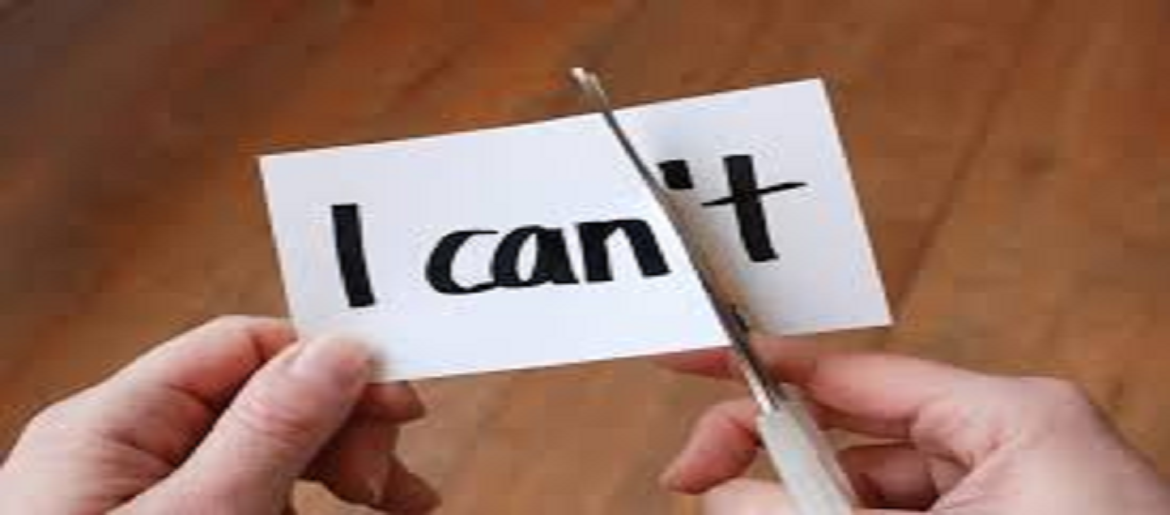

Whether you opt for a semi-colon, a comma and a fanboys, or a period between your independent clauses, remember that our job as writers is to make our writing

effortless for the readers. Banishing the comma splice—except in rare cases once you’ve mastered the art of banishing it—will lend clarity to your work, and you have better, accurate options.

Your readers will appreciate that!